"I was racing a (Nissan) 350z, and I was leading in front of him with my car, automatic at the time, very, very un-tuned, the mods I have now, half of them I didn’t have before. I still was able to do a decent job in holding him off. I held my own that night. I felt a sense of accomplishment. Especially the guy who got out of the car to speak to me says, “Is that a GS-R?” And no it wasn’t it was a regular GS , with a crappier engine, no V-TEC, with automatic (Transmission). It’s that experience, definitely one of them that makes what I do that much more enjoyable."

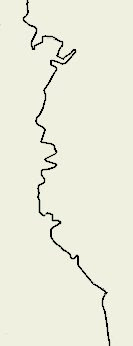

Grip drivers are more concerned about speed than anything. Cruisers are like grip drivers, but competition is less of a motivator. Not limited like the drifters, most car layouts work well with these styles of driving. The more talented drivers, with drift friendly cars, incorporate drifting to help themselves clear corners faster. Like the drifters, there are track events that are for grip drivers, but they’ve been around for quite some time. It’s very difficult to get into professional racing from a background in the mountains. So many drivers prefer driving on the mountains under their own terms. These hobbyists, like Kenji, never leave the mountains for legally sanctioned events. Though these drivers share the same roads as the drifters, they are worlds apart.

"I’d (Kenji) say tires are everything. Without tires, everything you have, you can have the best modifications. It won’t make any use unless you have tires."

Kenji considers himself a grip driver. He drives a 1999 Acura Integra GS with plenty of modifications. For our first interview, we met at my house back in early October. I had known him since we were both six years old. The reason why I wanted to talk to him about mountain driving was because he was doing it before me and still participates. The real gold was being able to go driving with him in San Jose at the end of October. I told him how nice the roads were up here, and he wanted to see the local drivers in action. I didn’t have a problem out driving some of the local drivers, but Kenji was trailing. By the end of the night, he had several close calls with the wall, and a blown engine. Now he’s having a GS-R engine installed and can’t wait to come back to San Jose.

"The fact that you can drive a piece of crap car that looks like shit, sizing it up next to the car next to you, it’s just totally, totally not capable of running against something that might have upwards of 100 to 200 horsepower against you, but when you can hold that guy off with what you got, the horsepower offset is amazing. That’s one of the big ones. That gives you a sense of pleasure, that’s one of the things I like about it."

Grip cars, like Kenji’s, are set up in a similar fashion to drift cars. Emphasis on the tires, suspension, and brakes are more important than engine power. Overall course time or head to head racing fuels the thrill that grip drivers feed off. Most of the drivers follow Initial D rules. It is a run and chase race where passing is not allowed. It mimics the tandem runs done in the finals of drifting competitions, but based off speed rather than style. If the lead car pulls away through the course it wins. If the chasing car keeps up, the chaser wins. If they constantly finishing the run nose to tail, they’ll repeat until the driver with less endurance or technique falls out. Sometimes parts start to fail after just one run from bad technique. Some of the grip drivers are against head to head racing. They’re the ones that run for time or for fun with the cruisers.

"There are times where I want to go, and more often than not, I don’t go because of the fact that there is the possibility I can get be pulled over by the police or have, worse case scenario, or even worse than that and actually crash. I would risk it, I don’t want to sound like an adrenaline junkie, which I’m not, but it’s the rush, it’s the satisfaction, it’s the enjoyment and joy that is involved."

The consequences of being caught by the police are more severe than the solo drifter. The worst violation a drifter can face, if they didn’t harm anyone, is reckless driving. It’s a 2 point misdemeanor violation. Grip drivers have more to worry about. If they’re driving head to head, they can have their cars taken away and spend the night in jail. According to the Whittier Police, the second violation can put the driver in jail for six months. With the added hype from drifting and the media, it makes it more risky for grip drivers and cruisers to go up to the mountains. However, grip drivers like Kenji share the same love for driving that drifters like Martin have. Even though it’s more risky to drive, both of them are often at the same mountain at different hours of the night.

Suspension: APEXi N1 99 Spec R Coilovers with 11k front/5k rear spring rates, JDM ITR rear lower control arms, front and rear Skunk 2 strut tower bars, ASR rear subframe brace with JDM ITR 23mm rear sway bar, Blox front camber kits

Suspension: APEXi N1 99 Spec R Coilovers with 11k front/5k rear spring rates, JDM ITR rear lower control arms, front and rear Skunk 2 strut tower bars, ASR rear subframe brace with JDM ITR 23mm rear sway bar, Blox front camber kits

Illegal mountain driving brings a variety of drivers together. Those who want to show off their car control abilities, those who want to race, and those who simply like driving there. Their mindsets and techniques put them in different categories in motorsports, but they have many things in common. They all spend every penny they have on their cars, drive on the same roads, and all compete in some sense. It’s easy to see how people group them in the same category. The best way to categorize it is that they are both ball sports. One is soccer, and the other is football. They can be played for fun or professionally. They’re not the same game, but they can be played on the same field and have goals.

Illegal mountain driving brings a variety of drivers together. Those who want to show off their car control abilities, those who want to race, and those who simply like driving there. Their mindsets and techniques put them in different categories in motorsports, but they have many things in common. They all spend every penny they have on their cars, drive on the same roads, and all compete in some sense. It’s easy to see how people group them in the same category. The best way to categorize it is that they are both ball sports. One is soccer, and the other is football. They can be played for fun or professionally. They’re not the same game, but they can be played on the same field and have goals.